Rob Gardiner and Sue Gardiner in conversation about Julian Dashper

28 January 2026

Julian Dashper speaking at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, during the 2007 survey exhibition To the Unknown New Zealander, with his artwork Here I Was Given, 1990-1991, Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

The following dialogue between Rob Gardiner and Sue Gardiner was originally published in Issue 4 of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki journal Reading Room as part of “Julian Dashper, 1960-2009: A Tribute”, edited by Simon Ingram with Wystan Curnow.

Sue Gardiner: Chartwell first purchased a work by Julian Dashper, Cass Altarpiece, in 1986. How did your interest in Julian Dashper's work develop?

Rob Gardiner: My attention to Julian's work would have came out of my general interest in reductive art, its place in New Zealand's art practice and his open, enthusiastic and generous sharing of thoughts around the conceptual structures which supported his work. The opportunity to follow the practice of an artist of his generation and stature was engaging and rewarding for me.

SG: When did you first meet him?

RG: It was during the acquisition of Cass at New Vision Gallery, Auckland in 1986. I remember the challenge for me in reconciling my limited knowledge and expectations of abstract expressionist painting with the deliberate mark making he used in the work that proffered a somewhat tongue-in-cheek revelation of that practice. Later I became more attuned to his methodologies and the depth of his thinking and intentions and found that I acquired a much deeper understanding of the Cass work as my appreciation of it has grown over time. Synergies between music, especially its recording and links with the visual arts later expanded the conceptual resources in his work.

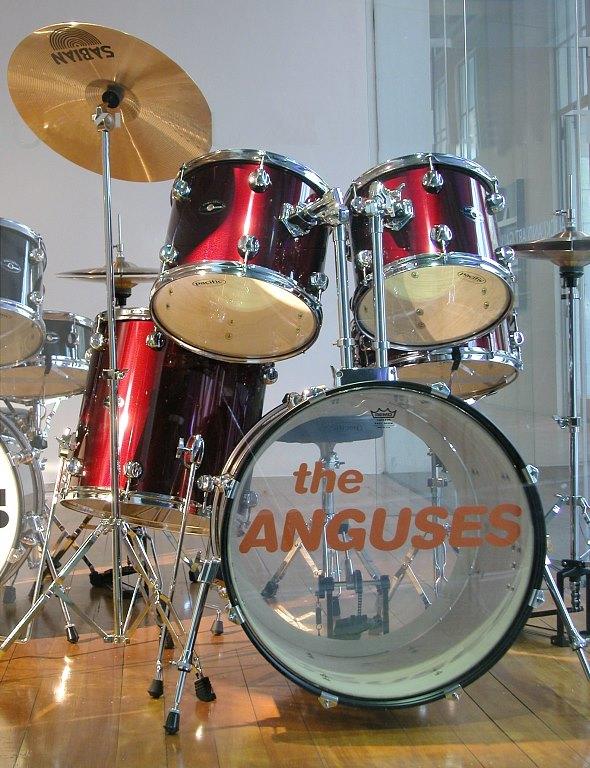

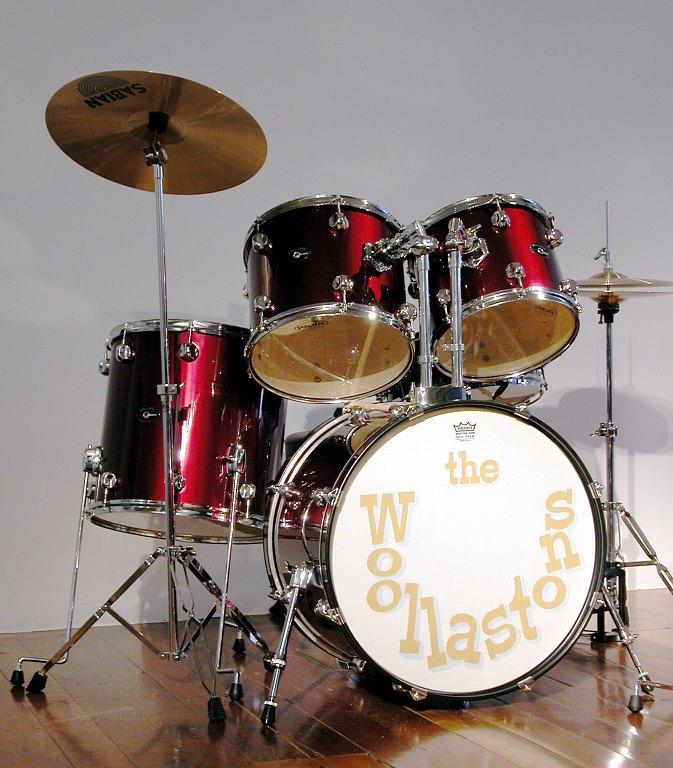

Then, in 1992, Chartwell purchased The Big Bang Theory and celebrated its joy in honouring New Zealand artists of importance within the rich idea of a series of drum kits, using found musical instruments as art works, providing a frame/facility for active promulgation of a visual artist's works and practices to a wider audience whilst making comment upon New Zealand art criticism at the same time. Then in 2007, Untitled, (The Painter's Mistake) joined The Big Bang Theory in the Collection and enabled revelation of the significance of the participating spectator, in this case, Hamish McKay, his Wellington dealer. Julian always had an awareness of the means by which his work was presented to the audience. In this case the work was extended by video recording and signalled his increasing interest in that medium.

SG: The reception of international visual art practices via reproductions runs as a thread through New Zealand art history, from Colin McCahon's interest in imported art magazines to Julian's playful interaction with Artforum through the placement of text and images in an issue of the magazine. How has his approach interested you?

RG: I found Julian's approach of significance from an early stage because he responded to the issue of distance as a New Zealand artist by active consideration of the phenomenon of art reproductions and their importance to the shaping of art knowledge in New Zealand. His realisation that those slides and reproduced images themselves were a medium that allowed him to reveal their objectness on the gallery wall and at the same time empower them to carry form and idea beyond New Zealand. We shared a belief in New Zealand as a place in which an artist could make art, find an audience and have a career, whilst maintaining a transient, global practice shared intimately with others principally through a network of artist run spaces and galleries. He was an artist who totally identified with, and responded in partnership with, the ideas of a selected group of artists who were important to him, both in a contemporary sense and in the history that informs the practice of reductive art today. I think I was prompted to consider more deeply the ideas and beliefs he shared with certain artists, honouring them in the process. This process also involved an increasing awareness of the nature of trans-Tasman reductive art practices, including artists such as John Nixon, George Johnson, Justin Andrews, Rose Nolan and many others.

Julian encouraged the collecting activities undertaken by the Chartwell Trust and understood that it was a means towards understanding and sharing knowledge about contemporary art making. He had an active interest in exhibition design and curatorial functions and was bubbling with ideas about showing work which revealed space/wall qualities and meanings whilst allowing an empowering focus on the work. He always seemed to be generous in his interest in and support of other artist's work and that was distinctive and impressive to me.

SG: In his practice, the formal and conceptual underpinnings of his work were reductive. In a set of acquisition notes titled "It is what it isn't", he noted "Take something away to make it stronger."

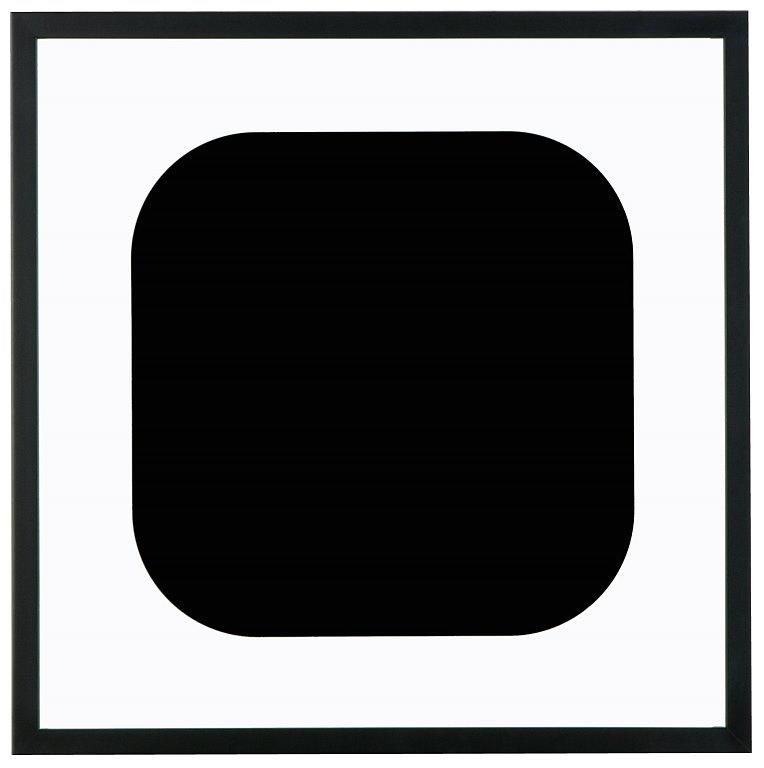

RG: He loved contemporary thought and researched intensely. For Julian, each visual element was given status and strength to be, and was respected for its identity as a carrier of meaning in itself. In this way his forms created an intense merger of intellectual idea and historic form. His rounded square paintings series which began in 1999 is a good example. Again in some acquisition notes, he himself explains that having first seen the MCA's 1998 Yves Klein show in Sydney, Australia, he considered Klein's monochromatic paintings to be the first truly abstract work in the world. He noted that Malevich had painted a white frame around the suprematist black square, concluding "therefore that the painting was still 'representational' in some sense." Julian then set about to make his own series of paintings based on the notion of the painted white frame. He wrote: "Make that the subject... the 'thing' that you never ever actually consider when you look at Malevich's infamous work... Of course, to make a painted white frame of something one first needs a space inside to define the outside. So I dreamt up more or less on the spot that very same day the shape of the rounded square… a shape whose sole purpose was, in my mind, simply to define a white frame around itself.”

Basic forms and ideas continued to evolve like this in provocative, creative ways over time as he emphasised clarity, restraint and simplification, reduced means, reduction of form, primary shapes, restricted colour and even restricted medium and touch. Thus his practice was influenced by modernism, minimalism, non-objective art, conceptual art, post-modern multi-media art, and generally practices that restricted representational images. His stories were art history stories embedded in those practices and his own.

SG: He once published a booklet of the art reviews that T.J. McNamara had written about his work in the New Zealand Herald over the years and sometimes made works that linked to his own birth date, 1960. How was his biography and career as an artist shown in his work?

RG: Of interest for me was Julian's linkage between his practice and his own progressive history as an art maker. He once said in some gallery notes on The Morphine Paintings, via email with Hamish McKay and provided to Chartwell as acquisition notes, that "everything I do as an artist is always intertwined with me as a person." Thus his understanding of himself within the artwork as an autobiographical form was recognised ultimately by the use of and publication of the CV as a work in time worthy of material presence as an exhibitable object on the gallery wall. Ultimately one followed and responded to the progression of his thinking within the forms of work he investigated. This was the challenge and was a big part of the interest in the works, watching and considering how they fitted within a personal practice and the New Zealand art environment. As a person, his interests in art, artists and in art history, particularly that of New Zealand art history, were embedded in the way he lived his life as a sharing, interacting communal human being. Communication and shared thinking completed the portfolio of his practice.