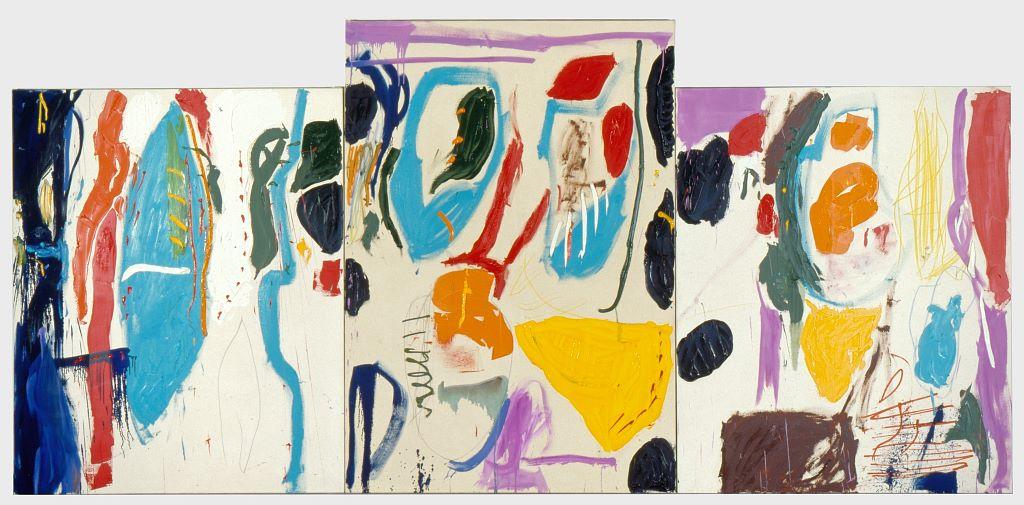

Cass Alterpiece by Julian Dashper (1986), Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

This essay is from Being, Seeing, Making, Thinking: 50 Years of the Chartwell Project, available for purchase here.

In 1961, Robert Rauschenberg sent a telegram to his gallerist in Paris, Iris Clert, that contained the immortal words: ‘This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so.’ By carrying the declarative force of its author to spark an image in the reader’s mind, this simple but iconoclastic statement changed the course of art. Now the bond between a subject and its visual representation was broken, granting artistic licence to the most arbitrary of signs.

I suspect Julian Dashper learnt this lesson and applied it through the course of his career. Certainly, Rauschenberg’s words come to mind as one confronts his Cass Altarpiece, 1986: ‘This is a portrait of Cass if I say so,’ he seems to be saying. Trusting the artist at his word, and despite the visual evidence – which consists of bright patches of colour, gestural marks and crudely drawn lines on raw canvas – I am taken to that small backcountry station and the famous painting by Rita Angus executed in 1936, exactly half a century earlier.

Despite there being no obvious visual clues to connect us to that source, Dashper turns the work into an object of reverence by invoking the early Christian devotional device of the triptych. With duly activated respect, we dwell on a different scene: no railway station, macrocarpa shelter belt, dry hills, shredded clouds, faceless bystander; no Madonna, crucified Christ, nor any saints; instead, an array of marks laid out before us. With evidentiary force, they show that someone with brush and pencil has been there, someone we are led by the painting’s title to believe is thinking about the artist who came before him, who is asking: ‘What does it mean to be a New Zealand painter?’

We know Dashper made a pilgrimage to Cass before he painted Cass Altarpiece. He took a photograph of the building that is still there beside the railway tracks. We know, too, that what caught his eye in the real moment was the small cross on the first aid box centred on the platform under the titular sign. This sparked a series of drawings, some of which were paired with the photograph, that play with the cross shape and focus on the negative space where four such crosses meet. Taking this knowledge to the finished painting, I see that negative detail swelling and stretching into patches of yellow and blue, forest green and indigo, liberated from the loaded symbol from whence it derived. This leads me to think that while Cass Altarpiece honours Rita Angus at a time when men still dominated our national canon, the painting is really an assertion of art’s freedom. Even as the artist pays homage to and draws from art’s history, conventions, traditions, rules and systems, he refuses to conform to the logic of representation, instead asserting his right to say and do as he pleases.